The magnificent setting of our state government for over two centuries has become an outstanding museum reflecting the history of Massachusetts since colonial times. Its spacious marble-floored corridors are lined with the portraits of Massachusetts governors and murals depicting our state's unique heritage. Adamses, Hancocks, Reveres, and Winthrops live on in statues and paintings recreating the glory of their times.

Of course, the State House is also a vital place of work for the leadership that guides our state today. You are welcome to observe the Senate and House of Representatives as they convene in their handsomely appointed chambers.

Past and present are partners in the Massachusetts State House. I cordially invite you to walk through the grand old building with a guided tour or on your own, and hope that your visit will be enjoyable, informative, and memorable.

Sincerely,

William Francis Galvin

Secretary of the Commonwealth

"The hub of the solar system..."

The Old State House

Oliver Wendell Holmes called the State House "the hub of the solar system,” but time has since altered the statement to "Boston is the hub of the universe." Today, Boston, not the State House, is called "The Hub."

The Early State House

In 1713, the old State House served as the seat of the Massachusetts government, located at the corner of Washington Street (formerly Cornhill Street) and State Street (formerly King Street). After the American Revolution, state leaders wanted a larger and more elegant home to better reflect the prosperous new republic, with enough space to accommodate an expanding government.

They selected a site for the new State House close to the summit of the south side of Beacon Hill, overlooking Boston Common and the Back Bay. The land originally served as a cow pasture for Revolutionary patriot and governor John Hancock.

Leaders chose a young native-born architect, Charles Bulfinch, to design the building. A public-minded citizen, Bulfinch served Boston as a selectman—and his buildings in Boston made a strong mark on the character of the city. He later contributed to the plans for the Capitol in Washington.

Bulfinch completed the State House project on January 11, 1798, and it was widely acclaimed as one of the more magnificent and well-situated buildings in the country. Its dome dominated the Boston skyline until the advent of the skyscraper.

The State House Today

Wrote a visitor to the State House in 1809: "It is a superb building and stands very High. I ventured up to the 1st Balcony, and tho' I risqued a fit of Gout by it, yet I was very much gratified by one of the most grand, picturesque & extensive Views that I have ever seen."

The golden dome of the State House serves as the official location of Boston to mapmakers. A sign that says "50 miles to Boston" really means fifty miles to the golden dome.

The Massachusetts State House is the oldest building on Beacon Hill. The building and its grounds cover two city blocks. The Bulfinch Front faces south, with its red brick walls, white pillars and trim, and golden dome catching the sun in every season.

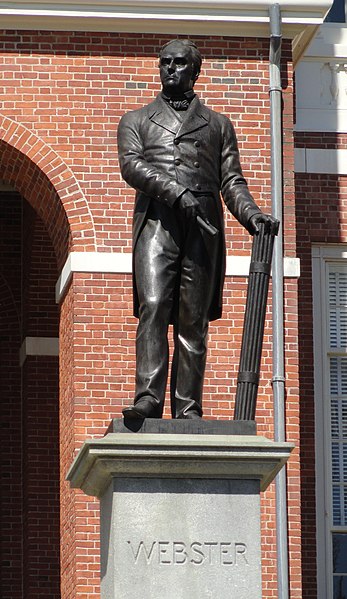

Below the central colonnade sit statues of orator Daniel Webster, educator Horace Mann, and Civil War general Joseph Hooker. In addition, the somber figures of Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer— religious martyrs of colonial days—rest on the lawns below the two State House wings.

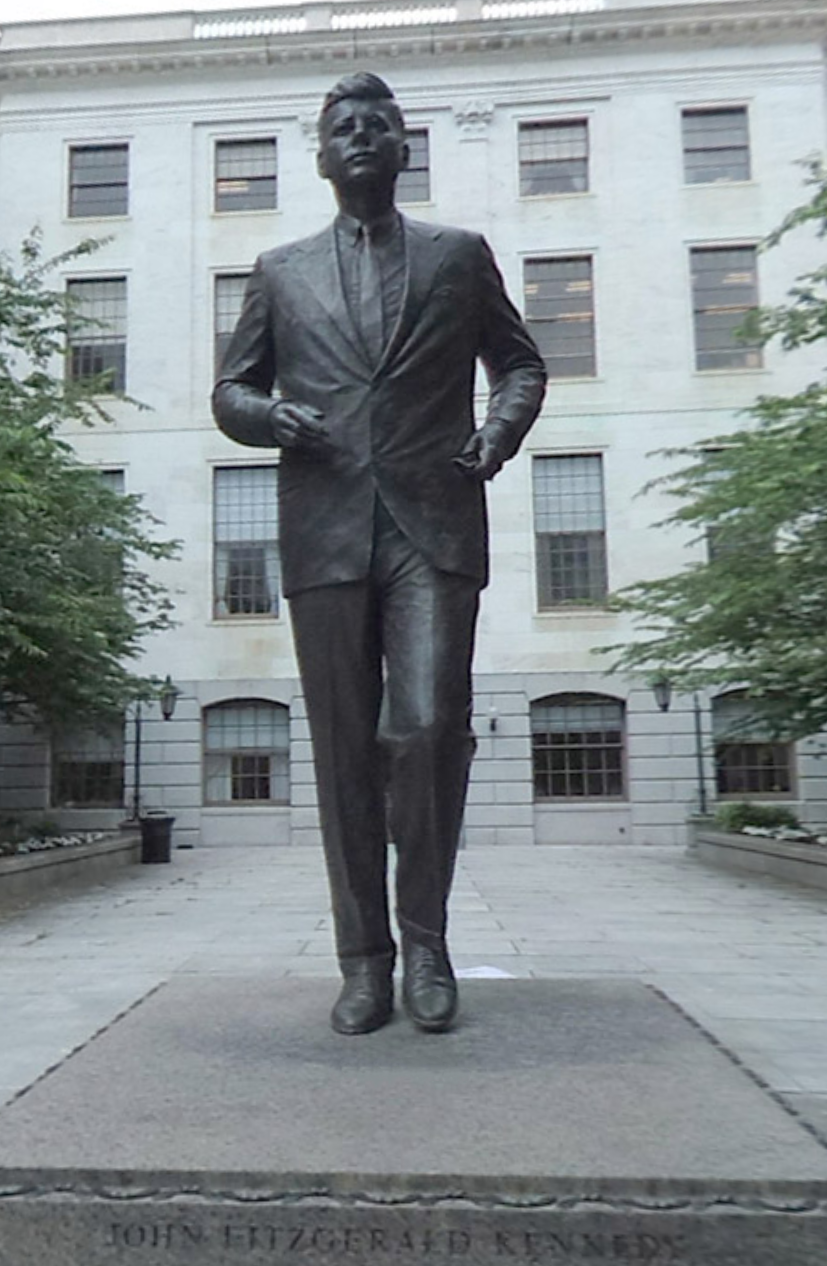

In the west wing plaza stands a statue of John F. Kennedy, the 35th President of the United States. A gift from the people of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, it was dedicated on May 29, 1990.

The newest addition to the State House art collection is Sheila de Bretteville and Susan Sellers' piece, "HEAR US," commissioned by the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities and permanently installed just outside of Doric Hall in 1999.

This work honors all Massachusetts women who were active in public life, recognizing the contributions of Dorothea Dix, Lucy Stone, Sarah Parker Remond, Josephine Ruffin, Mary Kenny O'Sullivan and Florence Luscomb. "HEAR US" presents these honorees in chronological order, beginning with Dorothea Dix, born at the very beginning of the 19th century, and ending with Florence Luscomb, who lived long enough to vote and run for office. A free interpretive brochure is available in a rack located beside the artwork.

The Legislative Branch

The Massachusetts Legislature, or General Court, was established in 1644. It has two branches, the 40 member Senate and the 160 member House of Representatives.

Massachusetts became a Commonwealth in 1780 when it adopted its remarkable Constitution. This document included a ground-breaking Declaration of Rights and was a model for the Constitution of the United States. It is, in fact, the oldest written constitution in effect in the world today, although it has been amended more than 100 times.

All Massachusetts citizens have the right of free petition and may have bills introduced by a legislator. Bills receive a public hearing and a committee recommendation. They must be read, debated, and passed in both the House and the Senate before they are sent to the governor to be signed into law or vetoed.

The Executive Branch

Massachusetts' chief executive officer, the governor, is assisted by a cabinet and a governor's council. Each cabinet secretary is appointed by the governor and is responsible for the implementation of policy in the departments under his or her jurisdiction. The eight members of the Governor's Council approve gubernatorial judicial appointments and pardons, as well as expenditures from the treasury.

A Tour of the Grounds of the Massachusetts State House

This section provides excerpts from the guided in-person tour. To learn how to book a tour yourself, visit our How do I book a tour? page.

Welcome to the grounds of the Massachusetts State House! As you walk around the outside of our state capitol, you will have a chance to see and learn about some unique architecture, sculptures of colorful characters from our historic past, some of the history-making moments which occurred right here and the monuments that remember them. Enjoy your visit!

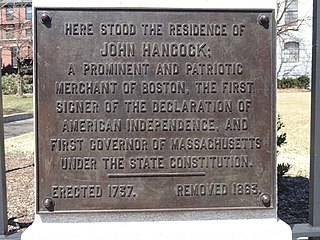

Begin your walking tour of the grounds on the sidewalk on Beacon St. at the Hancock House memorial plaque, located on the far west gate.

The area where you are now standing is Beacon Hill. Originally the highest point on the Shawmut peninsula, it was the first place in Boston to host a white settler in 1625, William Blackstone. Blackstone sold his land and small cottage to the Town of Boston. This was to be preserved as the Boston Common, a communal grazing and military training ground. This part of the early town remained rural and rough even through the eighteenth century when several wealthy patrons constructed country homes here, including Thomas Hancock in 1737. The Hancock House was considered one of the finest Georgian homes in Boston in its day, constructed of local stone and appointed with the finest British decor. John Hancock, signer of the Declaration of Independence and our first Governor lived here. Sadly, it was destroyed in 1863 against the cries of America’s first preservationists.

Going up the steps of the gate, move into the area of the West Lawn.

In 1795, the Hancock family sold the land behind and to the east of their house to the newly formed Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Once used as their family cow pasture, the state would use it as the site of its new State House.

Around the West Lawn, let’s take a look at some of the sculptures and other points of interest. The first one you come to on your left is Henry Cabot Lodge. Lodge was known by some as “Boston Incarnate.” Harvard educated, he was raised in the elite society of late-nineteenth century Boston. Over a political career of over 40 years, Lodge served as a State Representative and Senator, U.S. Representative and Senator, and held the chair at the Republican State Convention. When he held the floor in legislative sessions, he captivated all with his skilled speech, filled with classical allusions. He was also a scholar, and published historical works ranging from the history of Boston, to that of the Revolution, and all the way to the Spanish-American War, fought in his own day. The bronze sculpture was made in 1930 by Raymond Averill Porter.

Circling along the path brings you in front of the West Wing and a sculpture of Anne Hutchinson (1591-1643).

Anne Hutchinson was an early Boston colonist who was expelled from the colony because of her different religious views. She conflicted with ministers who preached that “good works” were a sign of individual holiness. She believed that people instead could only receive grace from God. She was also known to draw women to prayer meetings at her house because she gave women’s souls the same value as men’s souls. As a result, she was banished for heresy in 1638, fleeing to Rhode Island, and eventually staying in the New Netherland colony. In 1643, she and her family died tragically in a conflict between the Dutch colonists and the local Native Americans. This statue was sculpted by Cyrus Dallin in 1922, and given by the Anne Hutchinson Memorial Association and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs.

Completed in 1990, the sculpture of America’s thirty-fifth President was designed by Isabel McIlvain. Her goal was to show a youthful, magnetic leader striding forward, confident of his role and the prospects for America’s future. The sculpture is cast in bronze and rests on a pedestal of Prairie Green Canadian granite. Around the pedestal, Kennedy’s political career is recorded in inscriptions. Note that Kennedy never served in state government, nor have any of that family. President-elect Kennedy did visit the State House in January 1961 and addressed the General Court saying: “For what Pericles said to the Athenians has long been true of this Commonwealth: ‘We do not imitate—for we are a model to others.’” McIlvain placed eight bronze maple leaves and 68 seed pods on the pedestal, symbolizing the life cycle and the regeneration of Kennedy’s spirit and ideals. The sculpture serves to inspire future generations of public servants.

Find a spot to get a good view of the corner of the red brick part of the State House.

Here we have our first close up view of Charles Bulfinch’s State House, designed in 1787, and built between 1795 and 1798. From this angle, we can see the corner windows where the Governor can look out on the Common from his or her office. The executive chambers occupy the rooms on what is now the third floor, with the five arched windows facing west. The windows closer to the back of the original building are those of the Governor’s Council chamber. The building has changed over the years in many small ways. For example: the present first floor, in gray rusticated granite, is not original. Nor is the balustrade which graces the roofline. You can see above the balustrade the only two remaining chimneys on the Bulfinch building—originally there were ten. Before the mid-1800s, side entrances with small porches were where the center windows now are on the present second floor. Those second floor rooms originally housed the Treasurer and the Secretary of the Commonwealth.

Looking left along the West Wing addition, built in 1914-1917 by Sturgis, Chapman, and Andrews, you can see how the architects conservatively followed Bulfinch’s lead by continuing his style. The major difference is its construction in white Vermont marble. This wing mainly houses offices of the House of Representatives.

Walk back down the steps out to Beacon St., and turn left along the sidewalk to the central front gate.

From this vantage point, we can get a better feel for the graceful, elegant, yet commanding form which Bulfinch planned for the State House. Ordered and symmetrical, the building complements the incline of the hill, rising from loggia, to colonnade, to hip-roof and pediment, and finally the lantern-topped dome. Bulfinch was greatly influenced by Andrea Palladio, the late-Renaissance northern Italian architect, and also Sir William Chambers of London. Chambers and others like him were promoters of the Neo-Classical style then in vogue in Europe. The State House was the first building Bulfinch designed as an amateur architect upon his return to Boston from a grand tour of Europe. What he had witnessed, especially in London, he would transpose to the Boston landscape during America’s Federal period (1787-1818).

To note other changes in the appearance of the building, imagine the dome in its original state—wooden shingled and whitewashed. In 1802, Paul Revere and Sons covered it in copper. This was painted gray in time, then painted gold. In 1874, it was gilded in 23 karat gold leaf for the first time. During World War II, the dome was painted black to eliminate the possibility of moonlit reflections during blackouts—done to protect the building and city from bombing attacks. It was most recently gilded in 1997 at a cost of $300,000. A pine cone has always topped the lantern, reminding us of the importance of the lumber industry in the colony’s early days.

Walk partway up the stairs, to get an overview of the grounds.

Looking over the grounds, we can hearken back to times when the landscape appeared differently. Initially a 1.6 acre lot, a semi-circular drive came almost to the very front of the building from Beacon St., and a line of poplars was planted along the west property line. In 1826, Alexander Parris, a Boston architect and stylistic descendant of Bulfinch, designed and built the granite gates and wrought-iron fences which now greet visitors from Beacon St. The grounds have been regraded and enlarged through the years. Beacon Hill had developed further by 1914, including Hancock Avenue, which ran from present day Hancock St. to Beacon St. The houses there and the street were removed for the West Wing addition. The grounds by then included 6.7 acres. William Chapman, one of the architects of the East/West Wings, gave the grounds their present appearance during the years 1914-1919.

On the left…

Educator and statesman Horace Mann (1796-1859) is depicted in a statue by Emma Stebbins dating from 1865. Born on a farm in Franklin, Massachusetts, Mann was largely self-educated before college. He studied at Brown University and graduated in 1819 as valedictorian. Mann went on to earn a law degree and join a practice in Dedham. His legal career served as a starting point for his political one. He served as a State Representative and Senator, State Senate President, Secretary of the Board of Education, and U.S. Congressman. Mann was also President of Antioch College. His famous orations often touched upon education, democracy, freedom, and equality. Today he is remembered as the “Father of American public education” for his contributions in that area.

On the right…

Daniel Webster (1782-1852) stands proudly, sculpted in bronze by Hiram Powers in 1858. A graduate of Dartmouth College, Webster served as a lawyer and U.S. Representative from New Hampshire, in opposition to the War of 1812, before moving to Boston in 1817. As a lawyer in Boston, Webster became well known in the business community for promoting the development of interstate commerce and corporations. He argued more than 150 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, including the famous McCullouch vs. Maryland, prohibiting taxation of Federal institutions by states. Webster became a great advocate of nationalism. He continued to serve in public office as U.S. Representative from Massachusetts, as well as U.S. Senator, and Secretary of State during two separate tenures.

These steps and this front entrance have been the site of many an important ceremony. Governor Increase Sumner would have entered for the first time on January 11, 1798 in a procession from the Old State House. Presidents such as Monroe and Taft have made their official visits by entering the central doors, a privilege reserved for special occasions. Since the 1880s, a tradition known now as the “Long Walk” has been carried out by governors on their last day of the term of office. Begun by Gov. Benjamin Butler, for him it was a “Lone Walk,” bereft of supporters and well-wishers. Today, the governor still walks out alone, but is surrounded on the sidelines by hundreds of cheering onlookers. The incoming governor shakes hands and exchanges places with the former governor and makes his or her entrance at the same time. Heroes in America’s military past, such as the Marquis de Lafayette and Davy Crockett have made a visit.

In the early 1850s, Governor Kossuth of Hungary came to the U.S. to garner support for his country. He was given a fantastic welcome by Massachusetts, with banners running all across the colonnade proclaiming “Welcome!” and also the state motto. Flags billowed from lines tied between the State House and flagpoles on the street. Three temporary arches stretched over the stairs with inscriptions such as: “Religion, Education, Freedom—A Trinity for the World!” A crowd of thousands filled the lawn and a military guard on horseback lined the street.

Walk back onto the sidewalk and turn left, past the crosswalk, and turn left into the East Wing entrance.

An equestrian statue of General Joseph Hooker (1814-1879) from 1903 guards this entrance. The sculpture of Hooker himself was done by Daniel Chester French, the renowned Massachusetts sculptor who also did the sitting President Lincoln in the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. Edward C. Potter sculpted his horse; French only sculpted people. General Hooker, a native of Hadley, Massachusetts, graduated from West Point in 1837 and served in the Mexican War. At a meeting with President Lincoln during the Civil War, Hooker had the nerve to say: “I was at the Battle of Bull Run the other day, Mr. President, and it is no vanity in me to say that I am a damn sight better general than any you had on that field.” Lincoln made him a Brigadier-General, and later, Commander of the Army of the Potomac—the defender of Washington, D.C. He failed miserably in that post at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Virginia in 1863. His successes came at the Battle of Lookout Mountain in Georgia in November of 1863, and for this he is remembered. Civil War veterans of Massachusetts petitioned the General Court for the construction of this monument.

Turn right down the sidewalk to the Mary Dyer sculpture.

Mary Dyer was an early Boston Quaker who was hanged on Boston Common in 1660. She was charged only with being a Quaker. The sculpture was the work of Sylvia Shaw Judson and installed in 1959 at the bequest of Zenos H. Ellis, a descendant. It remembers a woman who made the ultimate sacrifice for the right to practice her religion. On the scaffold, she was offered the chance to live if only she stay away from Boston. She responded: “In obedience to the will of the Lord God I came and in His will I will abide faithful to death.” Judson inscribed Dyer’s own words on the sculpture: “Courage, compassion, and peace.”

Walk back to the East Wing plaza and enter the building. Exit by continuing straight past the information desk to the park behind the building.

NOTE: Ashburton Park and the Ashburton Park Entrance are closed for renovations through Fall 2023.

This is Ashburton Park, a historical reclamation of a park on this site in the early 1900s. The earlier park was erased to make way for a parking lot, and rebuilt only in 1990. The centerpiece is a recreation of Charles Bulfinch’s Beacon Hill Memorial Column. This one was recreated in the late 1800s, but Bulfinch’s stood on the original, higher peak of Beacon Hill from 1790 to 1811. Bulfinch himself carved the inscriptions recollecting Revolutionary events in chronology. The column, again reflecting what Bulfinch had seen in Europe, was taken down in 1811 when land was taken from Beacon Hill to fill in coves and the shoreline around the town. The height of the present column reflects the original height of the hill itself. Today’s column does have the original plaques carved by the architect.

Looking back at the building, the yellow brick rear of the State House looks far different in comparison with its older sibling in front, especially in its materials. This is the 1889-1895 Annex, designed in the Italian Renaissance Revival style by Charles Brigham. The exterior is in harmony with the Bulfinch front, but the interior is another style unto itself. The yellow brick was the fashion of the time, and the old Bulfinch front was painted yellow to match. There was once a semi-circular drive that came up by the curving steps in the center from Bowdoin St.

We hope you have enjoyed your walk around the grounds of the Massachusetts State House!