Parker-Harris Pottery

During the 18th century, several dozen potteries flourished on Charlestown’s waterfront near the Town Dock. These potteries produced lead-glazed earthenware called redware. Charlestown became one of the largest manufacturers of redware in New England and was well known for its popular “Charlestown Ware.”

Master potters were attracted to Charlestown because of its local clay, abundant wood to fuel the kilns, and easy access to the busy markets. Potteries clustered around the waterfront area because boats could transport the fragile pottery with less risk of breakage. Charlestown potters shipped their wares as far south as Connecticut and as far north as Maine.

The ceramic industry thrived between 1630 and 1880 and played an important role in the commercial growth of the Charlestown community, but the heyday of Charlestown’s redware potteries ended in 1775 with the Battle of Bunker Hill. At that time, public preferences were shifting from redware to salt-glazed stoneware. When most Charlestown businesses were destroyed by fire during the American Revolution, only a few potters rebuilt to carry on the manufacture of redware.

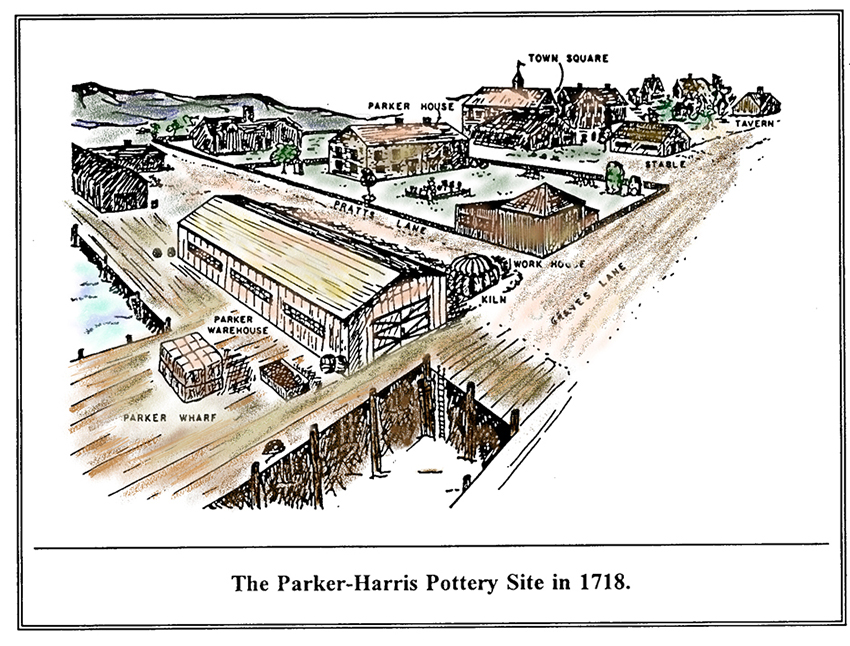

In 1986, archaeologists discovered the Parker-Harris Pottery site within the courtyard of the YMCA building at 32 City Square. Now a bustling urban area, it is hard to imagine that a simple house and potter’s shop stood here in the 18th century.

More than 200 years after its operation, the Parker-Harris Pottery is a notable historical site. It has provided extensive data on pottery as an important regional domestic industry. The site has taught archaeologists about local pottery production and a potter’s use of urban space. The pottery serves as an excellent example of the mixed residential and commercial space that typified the pre-Revolutionary potteries of Charlestown.

The drawing shown here is an artist’s rendition of what the Parker property may have looked like. Historical documents and lot plans have helped archaeologists to reconstruct the site’s layout during the pottery’s heyday.

Most potters lived and worked on the same lot. A typical lot included one or two kilns and kiln houses, a workshop, a glaze mill, and a warehouse. Extended families often owned many potteries where they trained apprentices who later opened their own shops.

Isaac Parker purchased this land in 1714, at the age of 22. He soon built a house and pottery facilities, including a shop, warehouse, and kiln. In 1715, he married Grace Hall, a native of Cambridge, England, with whom he had 11 children. Together Isaac and Grace Parker established what was to become one of Charlestown’s most successful potteries. They began by producing redware, a popular utilitarian ceramic used extensively throughout New England. Over the next several years the Parkers became one of the leading producers of this “Charlestown Ware.” With a successful family business in hand, the now wealthy Parker family became prominent in Charlestown and Boston affairs.

Around 1740, the Parkers expanded their operation to include stoneware production. They were the first pottery in New England to manufacture this durable ware. This was an ambitious project that was a significant event in the history of pottery making in Massachusetts. Until this time, stoneware was brought to Massachusetts from New York, Philadelphia, and Virginia.

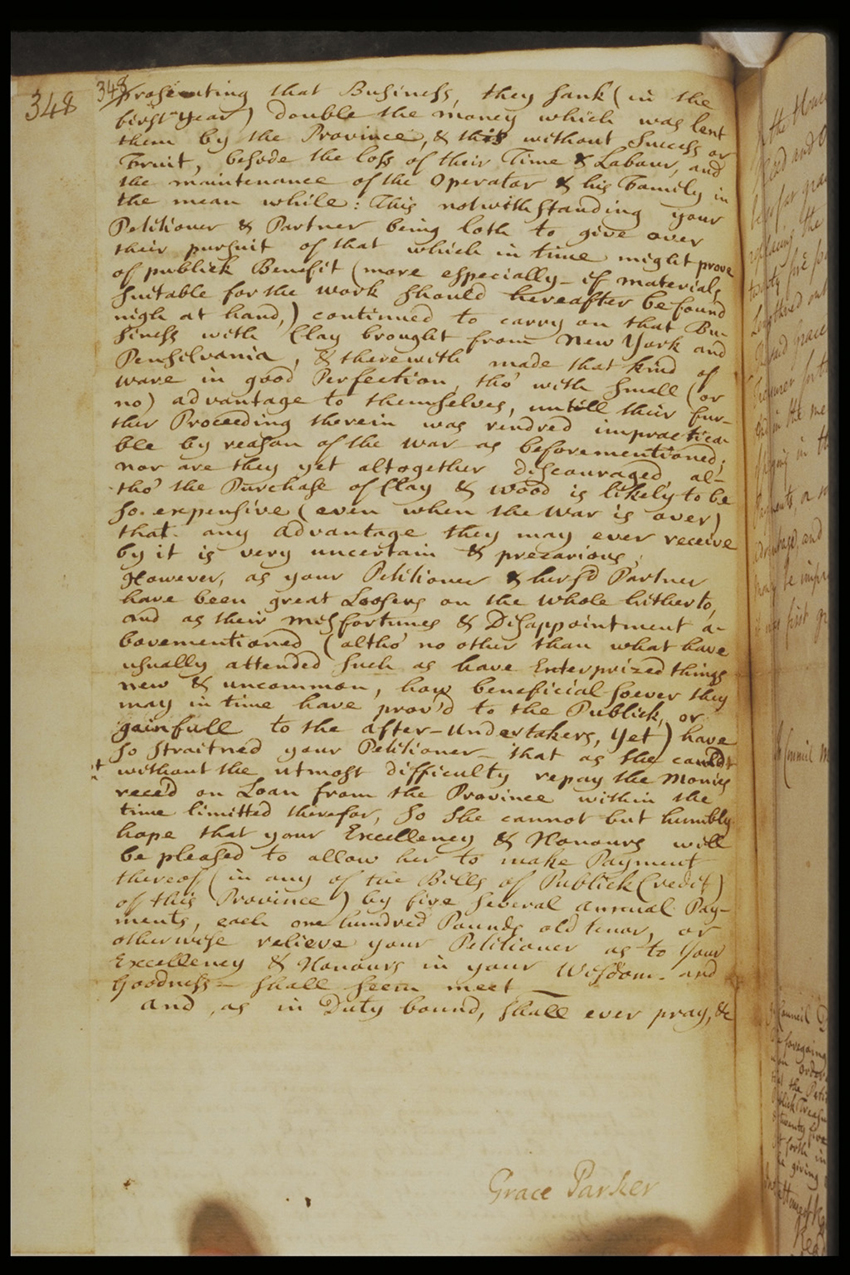

The production of stoneware, however, was not an easy endeavor for the Parkers. Isaac traveled to the southern colonies to learn more about its production, but most potters closely guarded the secrets of their technique. Next he hired Philadelphia potter James Duche to teach him the secrets of making stoneware. Once he had the necessary skills, Isaac found he didn’t have the right raw material. He discovered that New England clay could not be fired at a high enough temperature to produce perfect stoneware. To make good stoneware, he would have to import clay from New York or Philadelphia. To do this he took out loans and mortgaged six lots of his land to raise additional funds. Three weeks later, he died. His probate inventory shows that he left behind considerable wealth as well as considerable debt. His assets included a large home, silver, valuable textiles and paintings, furniture, two slaves, a servant, real estate, and potter’s tools.

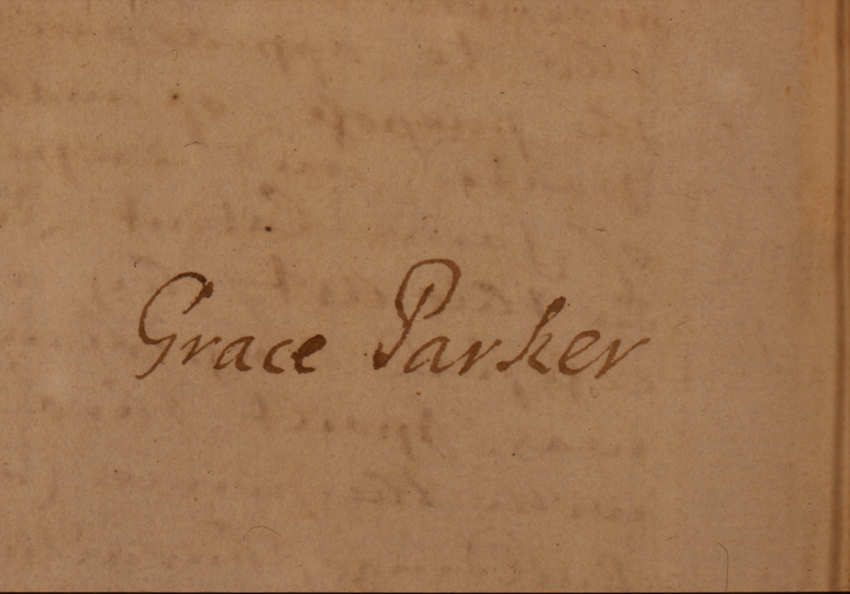

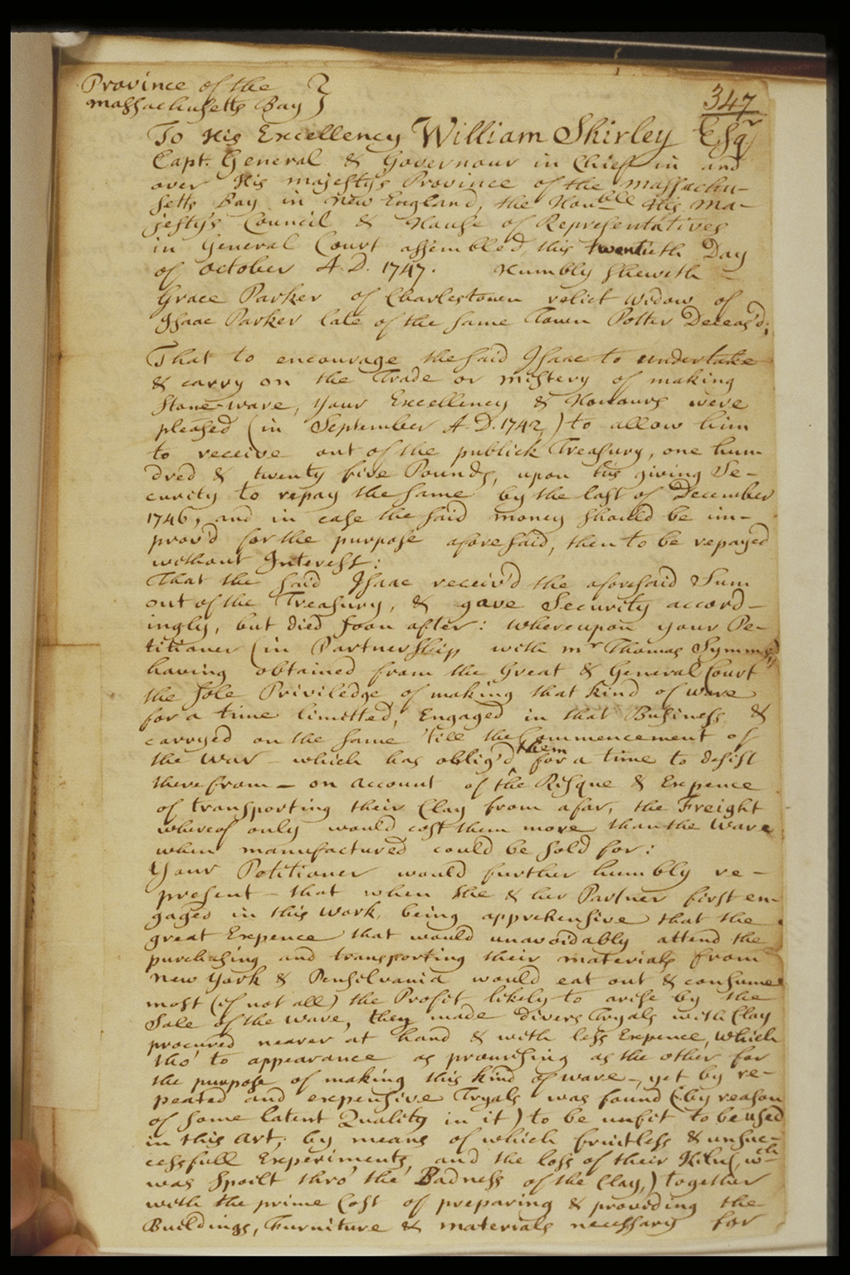

With Isaac’s sudden death in 1742, Grace inherited many burdens. She decided to go ahead with stoneware production while continuing to make redware. Her brother-in-law, Thomas Symmes, became her business partner. Grace directed the project and petitioned the General Court to keep the monopoly on stoneware production that had been granted to her late husband, Isaac. The stoneware venture was a costly one filled with trial and error, but Grace was ultimately successful.

Grace was a remarkable colonial woman who balanced the demands of business and motherhood. She was the first woman in New England to run a pottery in her own name. She had successful children, one became a goldsmith and the other graduated from Harvard and became a representative in Congress and Chief Justice of the Commonwealth. But stoneware making also took its toll on Grace Parker’s family. John Parker’s health failed due to prolonged exposure to chlorine gas from the salt-glazing process.

Grace Parker petitioned to “undertake and carry on the trade or mistery of making stoneware” after Isaac’s death. This venture was risky because the clay needed for stoneware production was not available locally and was costly to ship to Charlestown.

Grace Parker petitioned the Massachusetts General Court for the monopoly on stoneware production previously granted to her husband Isaac. This monopoly allowed the Parkers to have the sole privilege of making stoneware in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for 15 years.

For many years, John Parker ran the pottery for his mother. His account book recounts his daily business activities. By looking at John’s account book with the pottery fragments found at the site, archaeologists determined that mugs, bowls, baking pans, platters, and milk pans predominated, illustrating how early Bostonians prepared and served their food. Baking was the predominant method of food preparation in New England into the 18th century. The pans produced by the Parkers reflect the local demand for cookwares.

John Parker, whose health continued to deteriorate, ceased working as a potter in 1754 and sought less hazardous work. He eventually died in 1765 at age 40. All Parker Pottery production ended in 1754. Grace’s stoneware business partner, Thomas Symmes, died in July 1754, and Grace died five months later. Upon Grace’s death, potter Josiah Harris took over operations at the pottery. The pottery was destroyed by fire during the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775 and never rebuilt.

Ceramic Production

From the 17th to 19th centuries, redware was used extensively throughout the colonies. This thick-walled utilitarian earthenware was inexpensive to produce and buy. Its simple forms were easy to mass-produce, and it was sold locally throughout the Boston area and New England.

Redware was made from local clay collected from nearby riverbanks, typically in the late fall before the first freeze. The potter would first break up the raw clay and remove any rocks. Then the clay was mixed with water to make it more pliant, kneaded into large bricks, and stored under wet canvas.

Hollow vessels such as bowls, mugs, and pitchers were formed on a kick wheel, while plates were wheel thrown or hand pressed onto molds. Once completed, vessels were stacked on shelves and allowed to air dry for several days before glazing.

Vessels were glazed with a combination of lead oxide, sand, and water. Minerals were added to the glaze mixture to color it. To glaze only a vessel’s interior, the potter would pour glaze into the vessel, swirl it, and pour out the excess. If the entire vessel were to be glazed, the potter would simply dip it upside down into a vat of glaze. When fired, the glaze made the porous clay surface impervious to liquids.

Most vessels remained undecorated, but simple decorations were sometimes added prior to glazing. Designs consisted mainly of dots, lines, flowers, writing, or curves. They were applied by trailing fine, creamy clay lines of a different color across the vessel, using a “slip cup” as a dispenser. Vessels decorated in this manner were called “metropolitan ware” and imitated British designs. The Charlestown potters were successful imitators, probably at the expense of British earthenware manufacturers.

The Parker kiln sat on the northern edge of their warehouse lot. No physical evidence remains of it, however, due to modern 20th-century construction activities. It was likely a bottle updraft kiln, a type commonly used for firing lead-glazed earthenware and stoneware. The pottery fired the kiln one or more times during any given year and only when a sizeable number of dried wares were available to fill the kiln.

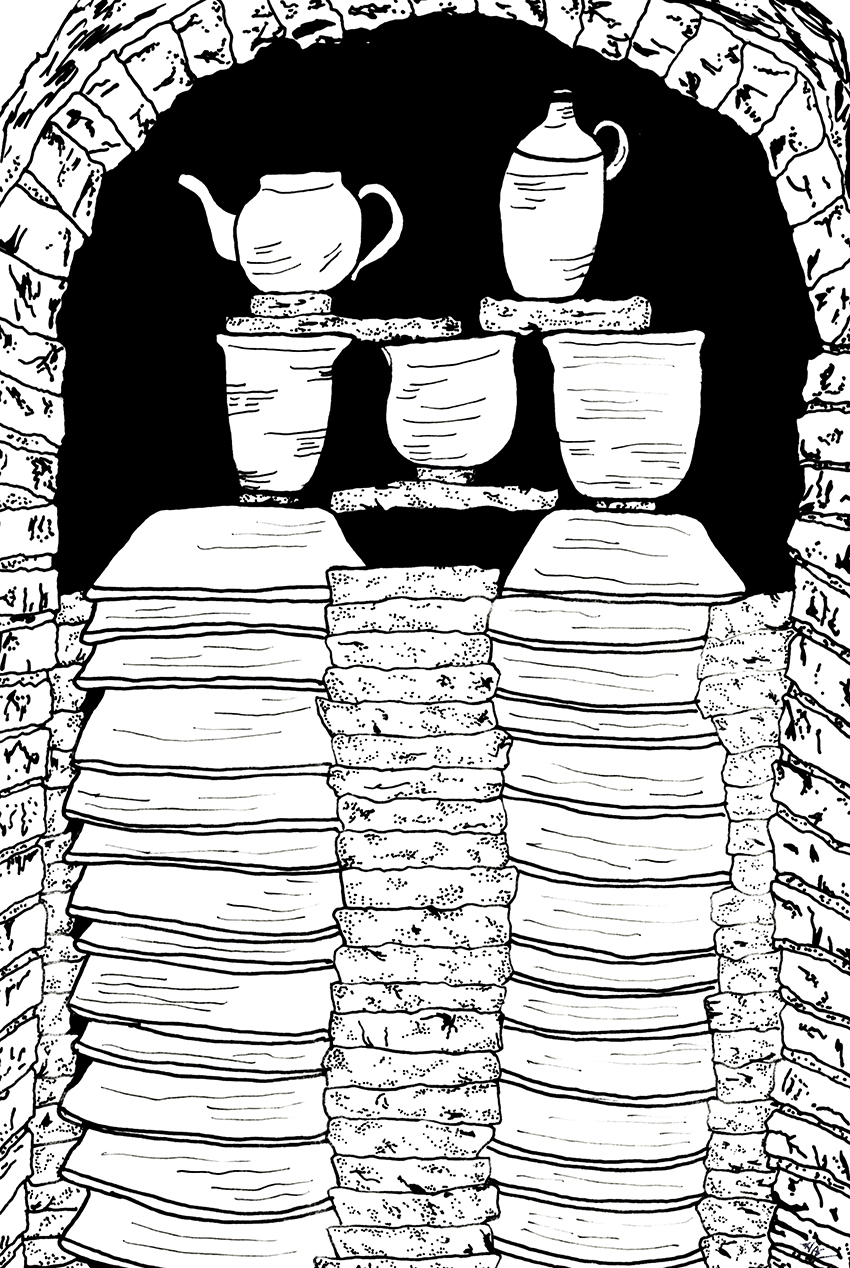

Wares were stacked on shelves around the kiln’s sides. The stacking of wares in a kiln to ensure the heat is evenly distributed is an art in itself. Kiln “furniture” is used to separate vessels. Archaeologists recovered many examples of kiln furniture from the site, including trivets, setting strips and tiles, and clay balls. Despite the precautions taken when stacking a kiln, accidents resulting in “wasters,” or pots destroyed and misshapen during firing, frequently happened.

When stacking a kiln, potters need to take great care to keep the vessels separated. Kiln furniture, including trivets, setting tiles, kiln balls, and setting strips are used to keep unfired vessels apart. Here you can see milk pans separated by setting tiles.

Potters fueled the kiln with a dry wood fire. Temperature was regulated by the type and quantity of wood burned. An adjustable “damper” at the top of the kiln regulated gas flow and temperature. The average time required to burn a kiln full of wares was three to four days.

Firing was carefully regulated by three to four men who tended the fires. The potter judged the end of the firing time by the color of the glowing pots seen through a tiny peephole in the kiln and the length and color of the flames escaping from the kiln. To check on the condition of the wares within the kiln, potters often used test pieces attached to long wires. The potter could withdraw them from the kiln at any given time to observe their firing state.

When the potter judged the firing to be finished, he put out the fire and sealed each one of the kiln’s openings to prevent cold air from rushing in and cracking the wares. The kiln cooled for four to six days before the potter removed the wares for sale.

Kilns are the ovens in which unbaked vessels are “cooked” or hardened and the glaze fixed to the bodies. Although the Parker’s business was 100 years earlier, their kiln may have been similar to this 19th-century style, bottle updraft kiln at Old Sturbridge Village.

Artifact Evidence

The artifacts recovered at the Parker site were badly fragmented and yielded no complete vessels. Archaeologists recovered mostly redware and very little evidence of the Parkers’ pioneering stoneware production. Archaeologists collected more than 24,000 fragments of redware from the Parker Pottery site. Analysis of these fragments, in conjunction with documentary evidence of the Parker Pottery, indicates that the Parker Pottery produced approximately 31 different types of redware vessels.

Most Massachusetts redwares were not marked by their makers and therefore are not usually attributable to a specific pottery. Redware is also very hard to date because ware styles remained similar for hundreds of years.

During the late 18th century, the use of redware began to decline in part because of the public outcry against the use of lead glaze, which caused serious health problems. Stoneware gradually became the ware of choice by the early 19th century.

Archaeologists also discovered kiln furniture. Potters use these small clay objects to prop and separate vessels when stacking the kiln to be fired. Kiln furniture was handmade on site by the potters. Kiln furniture is surprisingly informative; it helps archaeologists understand the firing process. Archaeologists can determine the relative positions of wares in a kiln by examining the wasters, kiln furniture, and glaze scars left on pots.

Artifacts Slideshow

See more artifacts from the Parker-Harris Pottery Site Exhibit