Cross Street Backlot

Katherine Nanny Naylor: A Personal Story from Colonial Boston

Katherine Wheelwright was born in Bilsby, Lincolnshire, England, in 1630. Six years later she arrived in Boston with her father Reverend John W. Wheelwright. In 1650 Katherine married Robert Nanny, a prosperous merchant. Together they had eight children. Robert Nanny died in 1663 leaving his estate, including the Cross Street house, to his children. Only two of their children lived to adulthood. Katherine outlived them both, and ownership of the home reverted back to her. Katherine married Edward Naylor, another wealthy merchant, soon after Robert died and they had two daughters. In 1671 she successfully sued for divorce from Edward on the grounds of domestic abuse including physical abuse, adultery, and an apparent poisoning attempt. Throughout her life Katherine was an independent and self-sufficient woman. In February of 1716 Katherine Nanny Naylor died at the age of 85.

In 1992, Central Artery archaeologists found Katherine Nanny Naylor’s privy at the Cross Street Back Lot site. This privy yielded an impressive collection of artifacts. The combination of rich documentary records and well-preserved archaeological remains from her house allow Katherine’s remarkable story to be told in intimate detail.

Both of Katherine’s husbands were wealthy merchants with business connections in Europe and the Caribbean. These business connections provided easy access to imported household goods such as fashionable ceramic tablewares and fancy foodstuffs. In the privy archeologists found rice imported from Madagascar, olive pits and an Iberian olive jar from Spain, and evidence of expensive imported spices. The array of international ceramics found in the privy tells us that Katherine set her table with decorative and expensive utensils and tablewares imported from Europe and Asia.

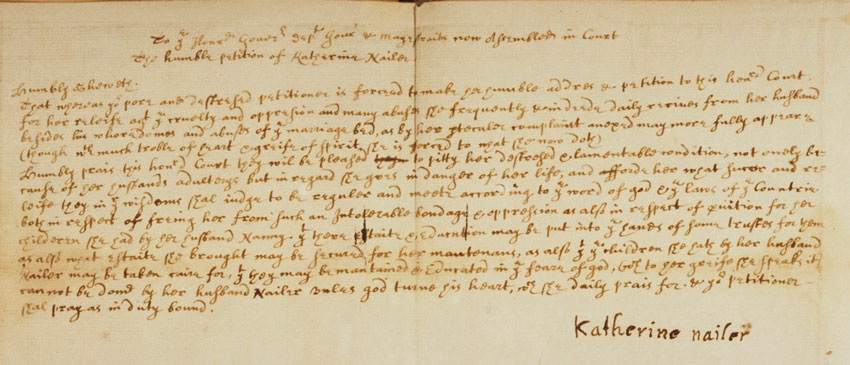

In 1671 Katherine filed for divorce from her second husband, Edward Naylor. From the 31 surviving pages of court records, which include Katherine’s own descriptions, a sordid tale of abuse and adultery emerges. Edward threw “earthen platters,” food, and chairs at family members and servants. The abuse was not directed at Katherine only; he also repeatedly “kikt [his daughter Lydia] down the garet stayres.” Some time before Katherine petitioned the court, Edward went to New Hampshire with Mary Read, a household servant pregnant with Edward’s child. The records also suggest that Mary Read may have tried to poison Katherine. Katherine reported getting sick after drinking some beer after neighbors reported seeing Mary buying henbane (a strong poison) and acting suspiciously.

In 1671 Katherine filed for divorce from her second husband, Edward Naylor. From the 31 surviving pages of court records, which include Katherine’s own descriptions, a sordid tale of abuse and adultery emerges. Edward threw “earthen platters,” food, and chairs at family members and servants. The abuse was not directed at Katherine only; he also repeatedly “kikt [his daughter Lydia] down the garet stayres.” Some time before Katherine petitioned the court, Edward went to New Hampshire with Mary Read, a household servant pregnant with Edward’s child. The records also suggest that Mary Read may have tried to poison Katherine. Katherine reported getting sick after drinking some beer after neighbors reported seeing Mary buying henbane (a strong poison) and acting suspiciously.

Eventually, a jury found Edward guilty of adultery and “inhuman carriage and guilty of flogging his wife and children.” He was banished to 10 miles beyond the city limits and had to petition the court for permission to return to get his clothes and personal possessions from Katherine.

The Cross Street Privy

A privy was an outdoor toilet commonly used before the age of indoor plumbing and municipal sewers. Privies also served as trash pits for household and kitchen waste in the absence of organized trash collection. Privies can provide archaeologists with a wealth of information about the daily lives of the families who used them. The artifacts shown on this page illustrate the range of information privies can contain, from foodways to recreation and interior decoration.

The Cross Street privy consisted of a below-ground, 5 x 8 ft, brick-lined vault supporting a wood structure containing two or three outhouse seats. This privy was in use from 1660–1716 by the family of Katherine Nanny Naylor. In 1652, a law was passed in Boston stating that a privy could not be constructed within 12 feet of a neighboring house unless it was vaulted with brick and at least 6 feet deep. There was a penalty of 20 shillings to the property owner if this ordinance was not followed. Although others ignored this ordinance, the builders of the Cross Street complied.

Because of the extraordinary variety of information preserved in the Cross Street privy, it has been called one of the most significant urban archaeological discoveries in North America from the early colonial period. In urban areas finding intact remains is very rare. It is rarer still to find organic materials, which in this case include everything from leather shoes to the eggs of parasites. With this data archaeologists can reconstruct daily life with remarkable detail.

The privy soil contained evidence of parasites that helped archaeologists determine that the people using the privy suffered from intestinal parasites. Although the parasites themselves had decomposed, their eggs, which are extremely resilient, were visible through a microscope. These parasites are relatively unknown in cities like Boston today but still infect people in areas without modern sanitation. Judging by the number of parasite eggs found in the privy, intestinal discomfort must have been an unfortunate aspect of everyday life in colonial Boston.

Colonial Fashion

Seventeenth-century fashion was extravagant. In Europe it was referred to as the century of ribbons, bows, and lace, but this was not the case in Boston. While 17th-century colonial dress was influenced by excessive European styles, New England Puritans viewed the flamboyant fashion as disorderly. Disorder in dress was a sign of disorder in people’s relationships to each other and to God. To enforce a modest and conservative style of dress among all inhabitants of the colony, the court established sumptuary laws.

Seventeenth-century fashion was extravagant. In Europe it was referred to as the century of ribbons, bows, and lace, but this was not the case in Boston. While 17th-century colonial dress was influenced by excessive European styles, New England Puritans viewed the flamboyant fashion as disorderly. Disorder in dress was a sign of disorder in people’s relationships to each other and to God. To enforce a modest and conservative style of dress among all inhabitants of the colony, the court established sumptuary laws.

The Boston Court passed its first sumptuary law “against fashions and costly apparel” on September 18, 1634. The laws forbade the purchase or wearing of woolen, silk, or linen garments with silver, gold, silk, or thread lace on them. By 1636 the court loosened control enough to allow a narrow binding of lace on linen garments. Despite the laws, colonists continued to purchase expensive fabrics and gold lace. In 1651 Massachusetts modified the legislation to distinguish between people of low estate (worth less than £200) and people of higher status (those with estates valued more than £200 as well as magistrates and other public officers). People of high estate were allowed to trim their garments in lace and fine silk and threads.

The Boston Court passed its first sumptuary law “against fashions and costly apparel” on September 18, 1634. The laws forbade the purchase or wearing of woolen, silk, or linen garments with silver, gold, silk, or thread lace on them. By 1636 the court loosened control enough to allow a narrow binding of lace on linen garments. Despite the laws, colonists continued to purchase expensive fabrics and gold lace. In 1651 Massachusetts modified the legislation to distinguish between people of low estate (worth less than £200) and people of higher status (those with estates valued more than £200 as well as magistrates and other public officers). People of high estate were allowed to trim their garments in lace and fine silk and threads.

Archaeologists recovered 158 fragments of silk and fine woolen textiles from the privy including a piece of 2-ply silk lace. From this item we can surmise that Katherine Nanny Naylor’s fashionably dressed family was either worth at least £200, or was willing to risk arrest.

Archaeologists recovered 158 fragments of silk and fine woolen textiles from the privy including a piece of 2-ply silk lace. From this item we can surmise that Katherine Nanny Naylor’s fashionably dressed family was either worth at least £200, or was willing to risk arrest.

Colonial Footwear

Footwear in 17th-century colonial America was an important commodity that was often in short supply. During the first half of the 17th century, the Massachusetts Bay Company ordered more shoes to be brought to New England to ease the shortage. Recognizing a new market, many shoemakers came to New England, where they received a charter of incorporation, forming one of the first trade guilds in New England. The guild’s primary function was to ensure that high-quality footwear was produced in the Boston area.

The shoes recovered from Katherine Nanny Naylor’s privy are some of the earliest examples of American-made footwear, dating to ca. 1670. These shoes were made 10 to 20 years after the Shoemakers of Boston charter.

The shoes are sophisticated and diverse in their design, suggesting that the charter succeeded in promoting good footwear. Katherine’s status and wealth gave her access to the highest quality merchandise even when shoes were in short supply in Boston.

The shoes are sophisticated and diverse in their design, suggesting that the charter succeeded in promoting good footwear. Katherine’s status and wealth gave her access to the highest quality merchandise even when shoes were in short supply in Boston.

Venetian Glass

Venetian glass was expensive. By Katherine’s time, glass makers across Europe copied the Venetian style. This small knob was likely from a perfume decanter. The twist would have been applied as decoration on a piece of fancy tableware.

A Colonial Bowling Ball

One of the most exciting finds in the Massachusetts Historical Commission’s Central Artery collection is this wood bowling ball. Recovered from the Cross Street privy, the ball is more appropriately called a lawn bowle. The 300-year-old bowle is the oldest known example in North America.

Lawn bowling is a very different game from the 10-pin and candle-pin bowling games that are popular today. This particular example is a “biased” lawn bowle. Lawn bowles are often weighted (or biased) to increase the curve that can be put on the bowle when it is rolled. This bowle is made of lathe-turned oak and is wheel shaped (as opposed to spherical). It is decorated on each of the flatter sides with a pair of incised concentric circles. The hole in the center of one side at one time held a lead weight that biased the bowle. The hole was probably covered with a decorative ivory or mother-of-pearl disc. Although the Boston lawn bowle was in good condition when thrown into the privy, its lead weight and decorative cover were missing, having been lost, removed, or recycled before the bowl was discarded.

In addition to its great age and rarity this is an exciting find because it sheds a little light on recreation in Puritan Boston. All ball sports, including lawn bowling, were common gambling games and the government of the Massachusetts Bay Colony tried to curtail them with new legislation. In 1650 a law was passed making it illegal to bowl in licensed taverns. The owner of the establishment would be fined 20 shillings if his guests were found playing at bowls and each player was fined 5 shillings.

By the early 1700s, however, the restrictions on bowling were lessened. The Boston News-Letter carried an advertisement in 1714 for the British Coffee House. It announced that the tavern now had a bowling green and that “all gentlemen, Merchants and others that have a Mind to Recreate themselves shall be well accommodated.”

“Another Recreation … hath been prescribed for a recreation to great Persons, and that is Bowling in which a man shall find great Art in choosing out his ground, & preventing the Winding, Hanging, and many turning advantages of the flame, whether it be in open Wide places, or in close allies; and in this sport the choosing of the bowle is the greatest cunning, your flat bowles being the best for close allies, your round byassed bowls for open Grounds of advantage, and your round bowles like a ball, for green swarths that are plain and level.”

-- Country Contentments 1652

This quote from a 17th-century guide to recreation titled Country Contentments describes how lawn bowles was played.

Most sports historians agree that modern lawn bowling and pin-bowling games are unrelated to historic lawn bowling. Lawn bowling is similar to the Italian game bocci. Games that require the player to roll a ball at pins are usually referred to as bowling, and there are a number of historical variations including nine pines, skittles, closh, loggats, and kayles.