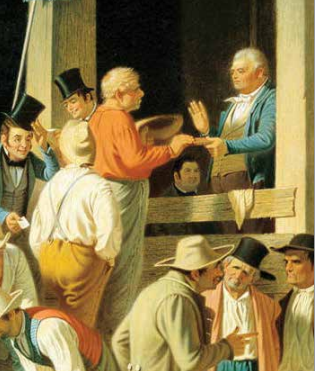

Through most of the nineteenth century, voting choices were stated publicly by voice (in many states) or by submitting names openly to election officials (common in Massachusetts). States did not print ballots for Election Day.

Viva Voce

The term means voting by voice. The laws of many states specified “viva voce” voting during this period.

That’s the Ticket

Newly formed political parties printed lists with the names of their candidates for various offices. Voters carried them to the polls and used them as a reference when voting. Because printed lists of party candidates resembled the lists of station stops for trains, the lists of favored candidates were called “tickets.”

Henshaw v. Foster

Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore, Whig

candidates for President and Vice President

in 1850. In Massachusetts many conservative

factory owners favored the Whig party

and opposed the secret ballot. Library of

Congress

Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore

An Act for the better Security of the Ballot, 1851.

Secret Ballot Controversy

The Whig Party – supported by many factory owners – favored public voting, openly declaring a choice. Reformers argued that a secret ballot would prevent intimidation of voters by employers. In 1851 the Massachusetts legislature mandated that the Secretary of State provide envelopes for voters to keep their choice confidential – a practice that was met with suspicion. “To say that the citizen should vote with a sealed bag…is an act of despotism,” wrote one critic. The requirement was later repealed.