The black community of Massachusetts contributed much to the Union war effort — men for the regiments, workers for local training camps, and even clothing and food for the troops.

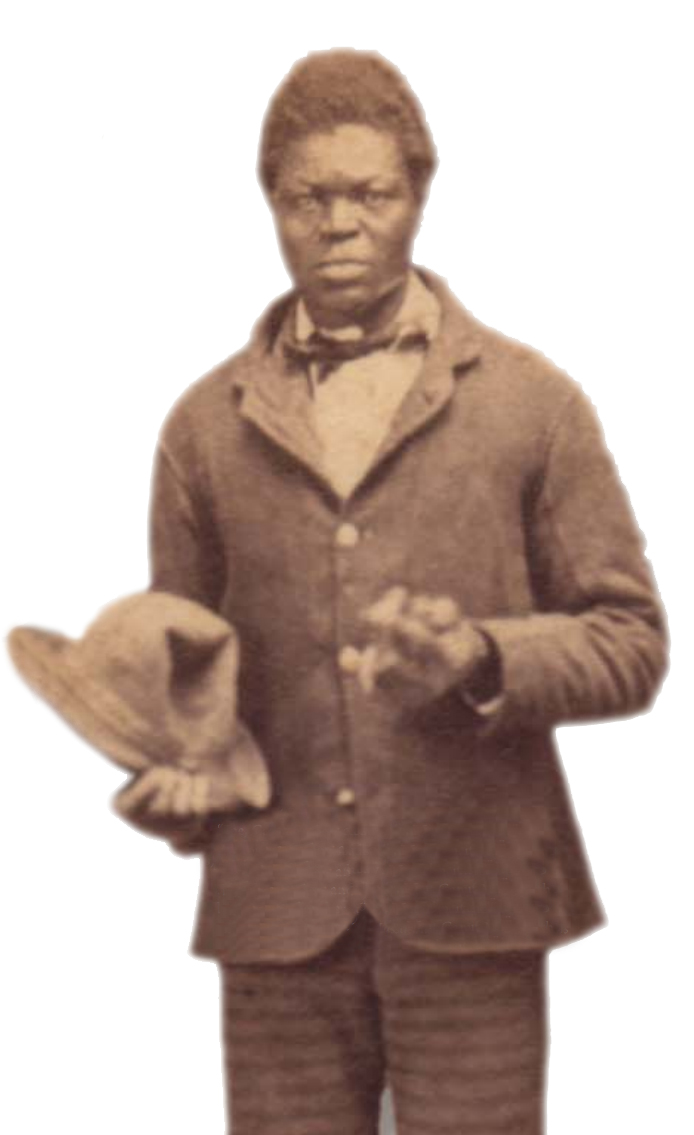

Although not clearly identified as such, it is likely that “Joe” was one of the many Massachusetts blacks who served as laborers and domestics at Camp Meigs both before and after the recruitment of the black regiments.

- Courtesy State Library of Massachusetts, Special Collections

Following federal approval, the African Meeting House in Boston became a central place for recruitment from the African-American community. In February 1863, local community members such as waiter Robert Johnson, abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and Lieutenant Colonel Edward Hallowell of the 54th Infantry Regiment spoke there, encouraging enlistment. Similar meetings occurred in New Bedford.

As enlistment increased, the community at home contributed to the war effort as best it could. Many of those who remained at home began to work as domestics and laborers at Camp Meigs at Readville. The Colored Ladies Relief Society presented a flag to the 54th Regiment as well as clothing and foodstuffs. Family members left at home struggled to support their families as soldiers went unpaid and state aid promised to their families was continually denied.

His son of the same name having reenlisted in the Massachusetts 54th Infantry, Joseph Kelson complained that the soldier received no pay and hence he himself was having difficulty supporting his grandchildren. It is unclear whether Joseph, Sr., ever received assistance from the state. His son died of disease less than a year later in Georgetown, South Carolina.

- Massachusetts Archives

- Photograph by T. C. Fitzgerald

African-American Meeting House, Boston, Massachusetts

The oldest standing African-American house of worship in the United States, it served as a center for recruitment for the Massachusetts black regiments during the Civil War.

In her continued effort to obtain the state aid promised to the families of enlistees of the black regiments, Mrs. Clark recounts her exasperating experiences and the constant denial of such aid by Massachusetts authorities, even though she had been married to her husband since 1858. Her request was eventually granted by the state auditor.

- Illustration by C.W. Reed, from Hardtack and Coffee, by John Billings